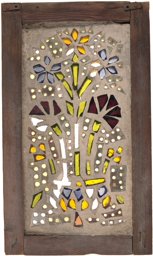

From an iconographic point of view, this stucco and glass window corresponds to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. Similar windows can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_7, IG_166, IG_178, IG_255, IG_290, IG_356). The representation of flowers in a vase is a widespread motif in Islamic arts. It can be found in numerous other media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, and textiles, over a long period of time, and in both sacred and profane contexts. Depending on the quality of the design, the type of flower cannot always be identified.

Among the most sophisticated examples of stucco and glass windows with the vase motif are those in the apartments of the Crown Prince at the Topkapı Sarayı (early 17th century, date of the windows uncertain) and those in the Sultan’s Lodge (Hünkâr Kasrı) of the Yeni Cami (1661–1663, date of the windows uncertain), both in Istanbul.

Stucco and glass windows with flowers in a vase also aroused the interest of Western artists and architects, as is attested by a significant number of book illustrations, sketches, and paintings (see for instance IG_43, IG_118, IG_149, IG_153, IG_437, IG_443, IG_461), as well as by the replicas of such windows installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_48, IG_49, IG_57–IG_59, IG_64, IG_91, IG_431).

Compared with other qamariyyāt of this type, the window discussed here is rather simple, due to its reduced number of flowers and the representation of only one recognizable species, the carnation. In other windows of this type, tulips, roses, and lilies are often depicted together with carnations (see for instance the windows mentioned above).

From a technical and iconographic point of view, it can be assumed that this window was made in an Egyptian workshop during the late Ottoman period. This hypothesis is supported by the results of the analysis of several stucco fragments from this window: both the stucco lattice and the top layer in which the pieces of glass are embedded (see Technique) are made of relatively coarse-grained gypsum plaster with many inclusions, including charcoal and brick particles. The properties of the plaster suggest artisanal production in smaller workshops like those that still exist in Egypt and the Maghreb today. The assumption of an Egyptian provenance is further confirmed by the results of the chemical analysis of a small number of pieces of coloured and colourless glass from this window. The four pieces of glass analysed all show relatively high concentrations of magnesium and potassium, suggesting that plant ash was used as a fluxing agent. The use of plant in glass production was particularly common in the Islamic world. In Europe, industrial soda ash was the usual flux in the production of sheet glass from the 18th century onwards. Somewhat contradictory, however, is the fact that some of the pieces of glass show the characteristics of cylinder-blown sheet glass, a technique that was unusual in artisanal glass production in Egypt, but widely used by the European glass industry. It is therefore possible that some of the coloured sheet glass used in this window was produced in a European glass-house. Interestingly, the Hungarian architect Max Herz (1856–1819) states in 1902 that sheet glass was imported to Egypt from Europe from the 19th century, because local sheet glass production had come to a standstill (Herz, 1902, p. 53).

According to the MIT Libraries’ records, this window was acquired by the Boston architect Arthur Rotch (1850–1894) together with three other qamariyyāt (IG_258, IG_259, IG_260) in the 1860s or 1870s. However, since he was still of a young age in the 1860s, we assume that he bought the windows at a later date. All four windows show the incised segmental arch and undecorated spandrels. These similarities support the assumption that they once formed a group of windows that were probably made in the same workshop. Traces of weathering on the surface of the latticework suggests that the window was exposed to the elements.

Arthur Rotch studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 1872 to 1873, when the American architect William Robert Ware (1832–1915) was head of the newly created Architectural School. Just as other MIT students, Rotch was a trainee at his teacher’s architectural firm, and he continued working at Ware & Van Brunt as a draftsman after completion of his studies in 1874 (Chewning, 1979, p. 26). Interestingly, William Robert Ware also had a collection of stucco and glass windows. He had purchased them in 1890 on the art market in Cairo. In 1893, he donated 17 qamariyyāt to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see IG_169, IG_171–IG_186). Due to the lack of documentation, it can only be assumed that the one knew about the other’s collection. It also remains unclear where Arthur Rotch’s enthusiasm for stucco and glass windows came from. After Rotch’s death, his sister Annie Lawrence Rotch (1850–1926), wife of Horatio Appleton Lamb, donated all four windows to the Department of Architecture at MIT as part of the Rotch Art Collection.