The design of the two panels of this window is reminiscent of a qamariyya drawn by the Bernese architect and draughtsman Theodor Zeerleder (1820–1868) in Cairo (IG_472) during his journeys to Egypt in 1848 and 1849/1850 (Bäbler/Bätschmann, 2006, pp. 57–80; Keller, 2020, pp. 55, 64).

Whereas the motif of a central six-pointed star in blue surrounded by six hexagons in red follows the Islamic prototype closely, the white hexagonal interlacing is a Western reinterpretation not found in traditional qamariyyāt.

During his stays in Cairo, Zeerleder examined several Ottoman houses, described them in his journal (BBB, Mss.h.h.XLIV.78), and made numerous sketches and watercolours of their architecture and furnishings, which are held today at the Burgerbibliothek Bern (see for instance IG_469–IG_473). The watercolour of a window in the sheikh’s house mentioned above, with its annotation of the colours of glass used, is a perfect example of Zeerleder’s detailed study of Cairo’s domestic architecture, which was to earn him a prestigious commission from Count Albert Alexander de Pourtalès (1812–1861), who had acquired Oberhofen Castle in 1844 and remodelled it in historicist style together with his father from 1848 onwards (Mülinen-Gurowski, 1859, p. 234; Germann 2002-a; Jordi 2004, pp. 25–39).

Like his father, Albert worked in the service of Prussia and travelled across Europe and the East as a diplomat. Between 1838 and 1851, he can be attested in Istanbul, where he worked first as secretary to the Prussian legation and, as of 1850, its envoy. This is probably also the reason for his enthusiasm for the East, which was expressed not only in the artefacts he brought back from the Ottoman Empire, but also in his wish to install an Arab-style smoking room, the so-called Selamlik, in Oberhofen Castle. In 1854, Albert entrusted the conception and execution of the Selamlik, which had probably already been begun in 1853 under the Neuchâtel architect James Victor Colin (1807–1886), to Zeerleder, who may have met de Pourtalès during his stay in Istanbul in September 1848 (Germann, 2002-b; Bäbler/Bätschmann, 2006, p. 168).

Based on his sketches and drawings from Cairo and Damascus, Zeerleder conceived a surprisingly faithful recreation of a traditional *qāʿa*, despite the absence of original pieces from the East (Giese 2015; Giese 2019, pp. 59–67). Nevertheless, when comparison is made with Islamic prototypes, significant differences can be recognized in the furnishings executed by local workshops.

This also applies to the windows, as already observed by Sarah Keller (Keller 2019, pp. 202–205). Hence, unlike the replicas of Islamic stucco and glass windows at the Maison Loti in Rochefort (IG_427–IG_431) or in Leighton House in London (IG_54–IG_59), the windows at Oberhofen Castle were executed in the Western stained glass technique, with lead cames instead of stucco to structure the design and hold the pieces of glass in place.

Even though the stained glass panels of this window are not signed, they may have been executed by the workshop of Ludwig Stantz (1801–1871), active in Bern from 1848, who made several other stained glass windows for Oberhofen Castle around 1850 (Tripet, 1894, p. 213; Heuberger, 2000, fig. 6), among them the historicist panels of the wooden cross-windows in the so-called Scharnachtalsaal, located in the first floor of the medieval keep.

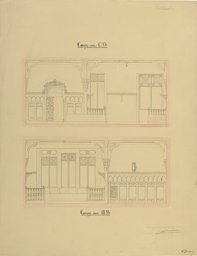

A preliminary design for the Selamlik by Zeerleder, preserved at the Burgerbibliothek Bern and dating from around 1854 (BBB, Gr. B. 322) (see Linked objects and images) shows large-scale star motifs instead of the interlaced hexagons and stars of the two stained glass panels discussed here. We can therefore assume that the design of the windows was changed during the construction process (Keller 2020, p. 55).