In 1895, Max Herz compiled a catalogue of the objects of the Museum of Arab Art in Cairo, founded in 1881. Among many other objects, he lists twenty-two stucco and glass windows held in the collection. For three of them, of hexagonal form, he names the original building from where they were taken: the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafiʿi. He also comments on the history of the stucco and glass windows in general and distinguishes two different types of manufacture. After Herz, the older technique (7th–8th centuries AH / 13th–14th CE) consisted in applying strips of plaster around the pieces of glass set on the reverse of the perforated stucco plate; the glass used was always very thick. Herz names three examples with such windows: the qubbat Al-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub, and the mosques of Sultan Qalawun and Sanjar al-Jawli. The window fragments of the qubbat Al-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub, which date to the 7th century AH / 13th CE, were considered by Herz to be the oldest in Cairo (Herz, 1895, p. 68). In 1952, Creswell noted (vol. 1, pp. 255–256, pl. 6b) that an even older stucco and glass window was preserved on the southern side of the small domed pavilion added to the entrance of the courtyard of Al-Azhar Mosque, dating to the middle of the 6th century AH / 12th CE. He also pointed to the windows in the dome of the Mausoleum of the ʿAbbasid Caliphs, created before 640 AH / 1242 CE (Creswell, 1952/60, vol. 2, p. 91, pl. 30a; see also Flood, 1993, p. 86). More recent research on archaeological finds has revealed that in Sabra al-Mansuriyya (Ifriqiya) the ‘sandwich’ technique was already in use in the 4–5th centuries AH / 10th–11th CE (Foy, 2017, p. 70).

Herz reports how in the course of the 8th century AH / 14th CE a slightly different technique was developed: the pieces of glass were fixed to the back of the cut-out plate by pouring plaster between them. The glass used was sometimes very thin. As early examples, Herz names the Mosque of Sultan Barquq, the buildings erected under Sultan Qaytbay, the Madrasa of Abu Bakr Muzhir, and the Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi. For the glasses, which were coloured in the body, he observed three shades of red and blue, and two shades of green and yellow. The glass paste contains small air bubbles and from the frequent presence of rounded edges of the pieces of glass, Herz concluded that the pieces of glass were made out of quite small panes (Herz, 1895, pp. 7–8, 28, 59).

Flood (1993, pp. 146–147) later confirmed and detailed this division into an older and a younger technique. However, archaeological finds in Fostat (Istabl’ Antar) have revealed that stucco and glass windows with thin layers of stucco applied to the back already existed in the 4–5th centuries AH / 10th–11th CE (Foy, 2005, p. 133).

Herz furthermore observed that the stucco and glass windows of the last centuries were of inferior quality in comparison with older specimens. He found it a matter of regret that the designs had become poor and the execution crude. He saw one reason for this in the diminished availability of glass. As there was no more locally produced glass, there was no longer a large choice of local products to attain the harmonious colour effects. Only the glass that was imported and available on the market could be used.

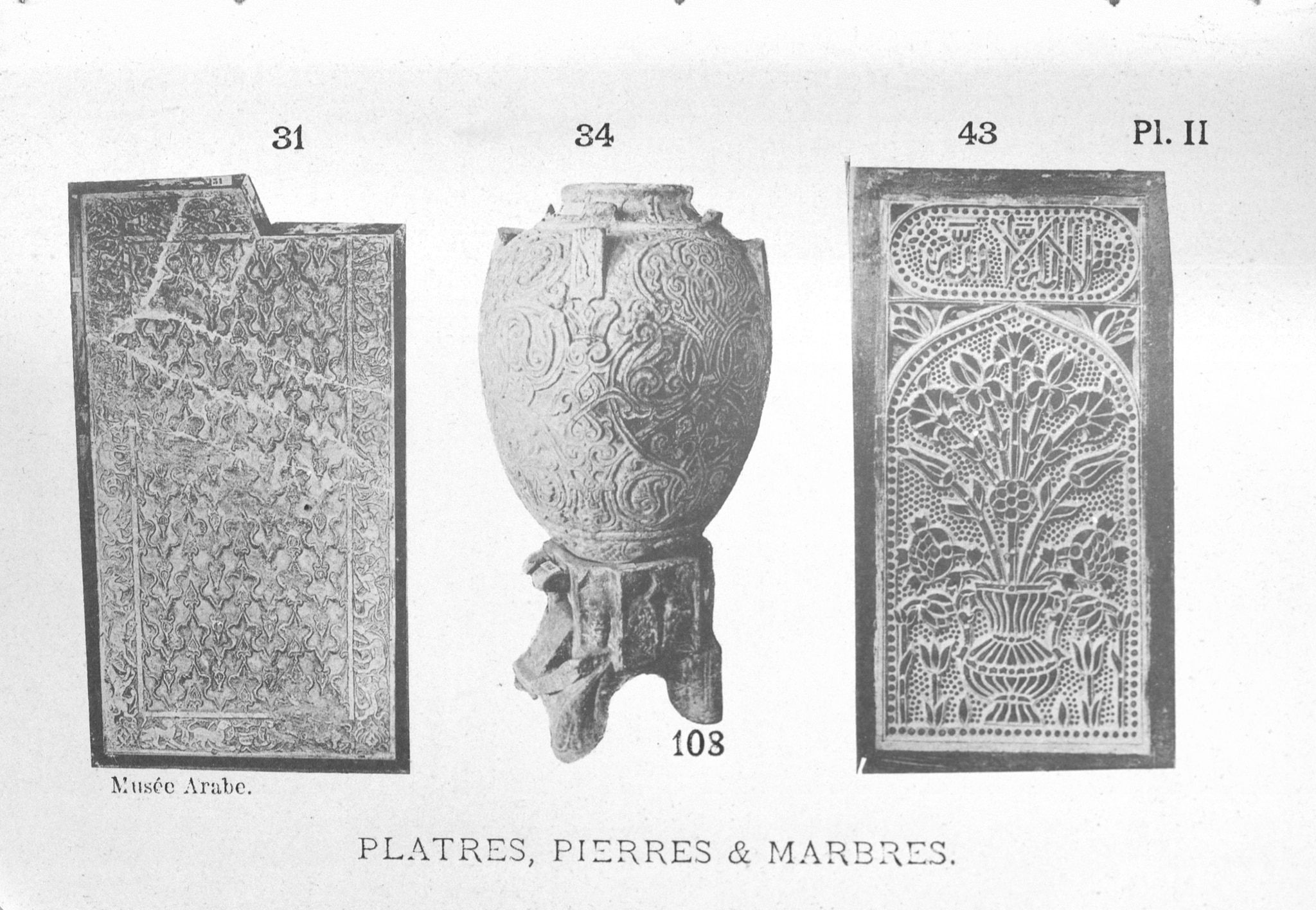

Herz does not directly comment on the stucco and glass window illustrated (it has the number 43, but the caption under this number refers to a different object). The specimen, showing a vase, is still preserved in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo (387/2). The same window was published by Julius Franz in 1903 (p. 115) and by Henri Saladin and Gaston Migeon in 1907 (vol. 2, p. 369). The photograph was taken by the photographer Gabriel Lekegian (IG_480). Migeon dated the stucco and glass window to the 8th–9th centuries AH / 14th–15th CE, without detailing his arguments. Today in the museum the window is dated to the 11th–12th centuries AH / 17th–18th. The motif of a vase was used in Cairo from the beginning of the Ottoman period in the 10th century AH / 16th CE (Flood, 1993, p. 171; see the specimens from the 13th century AH / 19th CE, IG_1; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 223/1894). Since no information is available on the origin of the window, its date cannot be further narrowed down.

The same window was drawn by Jules Bourgoin, during his stay in Cairo 1881–1884 (IG_461).

In 1896, the catalogue of the Museum of Arab Art was translated by Stanley Lane Poole and published in London by Bernard Quaritch. A second, revised edition appeared in 1906 (Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Cairo) and was also translated into English (National Printing Department, Cairo, 1907). It includes two further illustrations of stucco and glass windows: fig. 17 shows a window from the Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi (886 AH / 1481 CE), and pl. IV a mashrabiyya with a row of stucco and glass windows with large colourless glass panes in the middle.