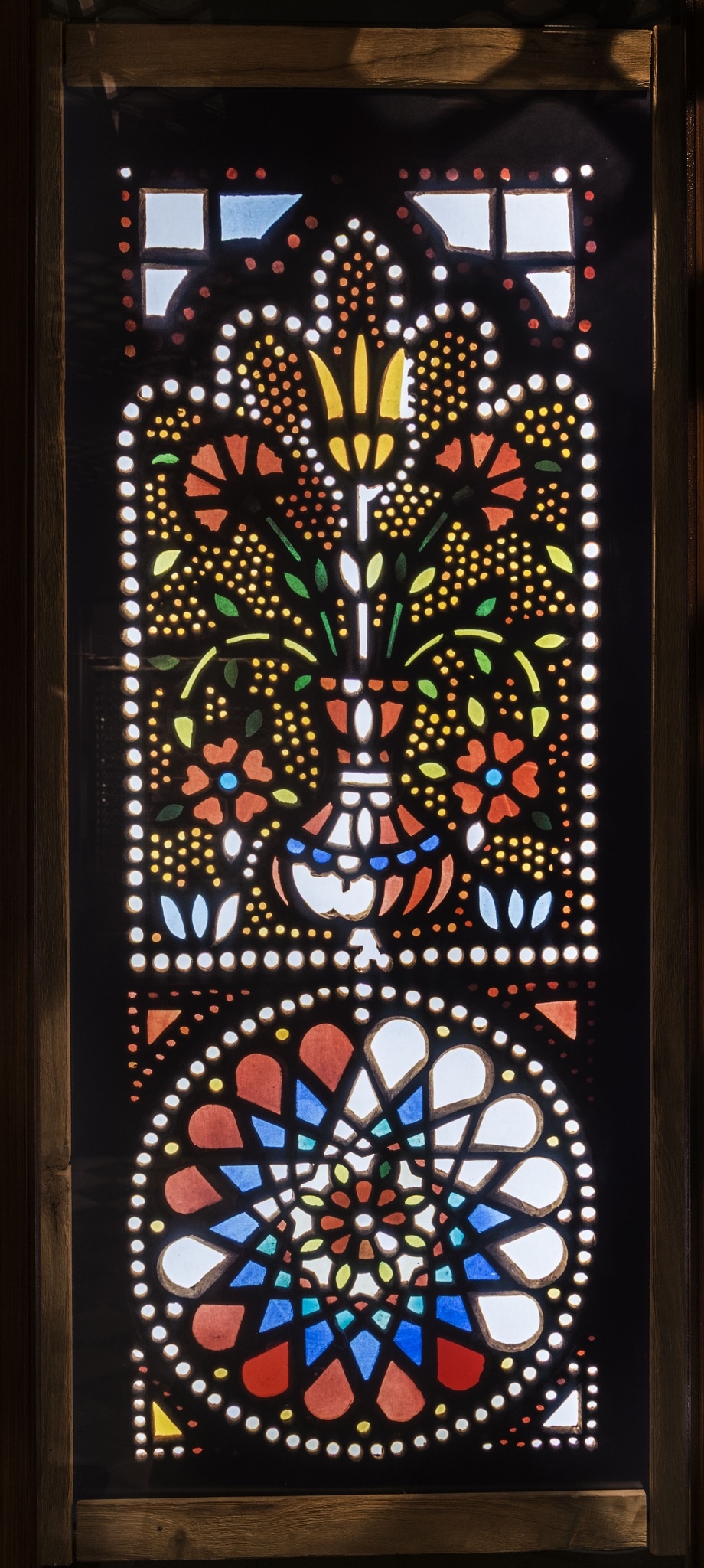

This stucco and glass window is a rare example of a completely preserved specimen, where the individual motifs that traditionally make up such windows have not been cut apart. Both motifs are standard for the qamariyyāt that were widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. The upper motif stands out from the majority of windows of the same type, on account of the precise cutting of the latticework. It shows flowers in a vase, a widespread motif in Islamic arts across numerous media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, textiles, and stucco and glass windows, and over a long period of time, in both sacred and profane contexts. Depending on the quality of the representation, the flower species depicted (carnations, lilies, roses, tulips) are not always recognizable. Among the most sophisticated examples are the stucco and glass windows from the apartments of the Crown Prince at the Topkapı Sarayı (early 17th century, date of the windows uncertain) and the Sultan’s Lodge (hünkâr kasrı) of the Yeni Cami (1661–1663, date of the windows uncertain), both in Istanbul.

Windows with the same motif can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_7, IG_178, IG_255, IG_356). The representation of flowers in a vase also aroused the interest of Western artists and architects, as is attested by a significant number of book illustrations, sketches, and paintings (see for instance IG_43, IG_118, IG_149, IG_153, IG_437, IG_443, IG_461), as well as by the replicas of such windows installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_48, IG_49, IG_57–IG_59, IG_64, IG_91, IG_431).

The lower motif with its sixteen-point star enclosing an eight-petalled flower shows a well documented motif as well. Similar compositions are held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (IG_186) and (in a slightly different version) at the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art in Athens (IG_353). They are also illustrated in Gustave Le Bon’s La Civilisation des Arabes of 1884 (IG_192) and depicted in several sketches and paintings (see for instance IG_104, IG_118, IG_444). Symmetrically designed flowers and stars are a recurring element in Islamic ornamentation across time and media. However, the insertion of a flower within a star is uncommon in the western Islamic world (al-Andalus and Maghreb), where star ornamentation is always restricted to purely geometric forms (IG_170, IG_363, IG_364, IG_366).

Before entering the collection of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm in 1899, the stucco and glass window formed part of the collection of Islamic art belonging to Frederik Robert Martin (1868–1933). It was presented together with other stucco and glass windows in an exhibition dedicated to Martin’s collection at the General Art and Industrial Exposition of Stockholm in 1897 (Martins Sammlung 1897). A photograph published in the exhibition catalogue (IG_403, IG_405) shows a window of the same design, which may very likely be the window discussed here. According to the catalogue, the window depicted originates from a mosque in Cairo and dates to the 16th century (Martins Sammlung 1897, p. 7). However, the stated origin and date must be questioned for various reasons: The outline of the polylobed arch is reminicent of the so-called Ottoman Baroque, emerged in the mid-18th century, and the design of the spandrels refers to a new type of stucco and glass windows, which was introduced in Istanbul around the same period and is characterised by large pieces of colourless and coloured glass. Even though it can be assumed that the Stockholm window was made in a workshop in Egypt, the apparent influences from the Ottoman capital support a dating to the 18th or 19th century. Also the good state of preservation of the window argues against its dating to the 16th century. The latticework and the frame lack any trace of weathering, which would have occurred if the window had actually been installed in a Cairene mosque for more than three centuries.

In the photograph of 1897, most of the pieces of glass are missing. If the window depicted is identical with the window discussed here, then the lost pieces must have been replaced with new glass shortly before or after the window entered the collection of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. Most of the pieces of glass show elongated parallel bubbles suggesting that the sheet glass was produced using the broad-sheet method. On some pieces, the straight edges of the rectangular glass sheets are preserved, corroborating this hypothesis. However, the turquoise pieces of glass show concentric lines that are characteristic features of glass produced using the crown glass process, a technique that was predominant in the Islamic world up to the 19th century. It is therefore possible that this piece is original and that the glass as well as the window were produced in Egypt.