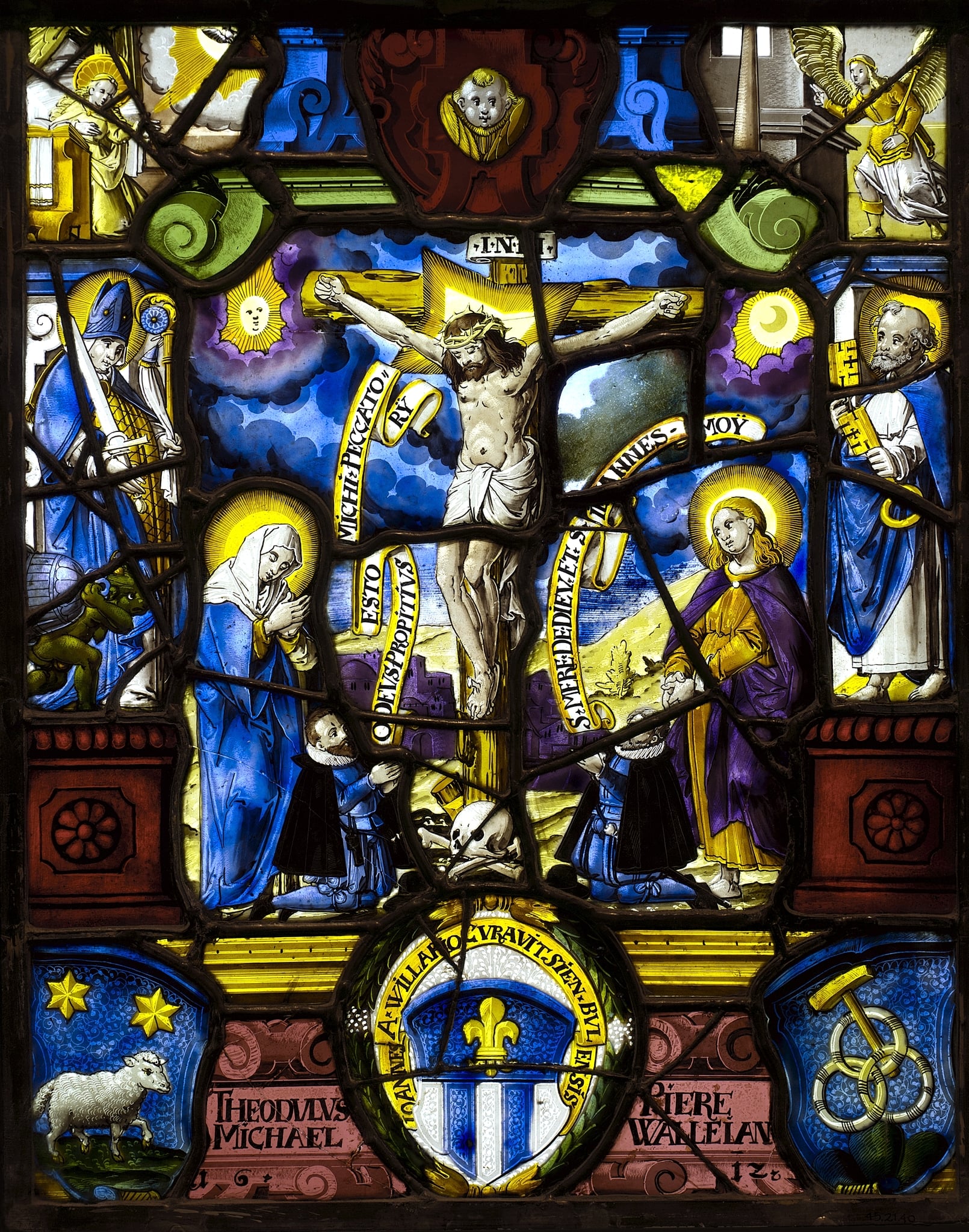

The panel presents a confessional statement by two male donors meditating at the foot of the cross. Each is addressing the images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. John that they see in their mind’s eye. Their prayers, made explicit by the inscriptions below, are uttered both in Latin, the official language of the Catholic Church, and in the French vernacular. The Crucifixion is portrayed vividly, set against a cloudy landscape of blue, purple and yellow. In the center, Christ is flanked by images of the sun and moon. These are symbols common since at least Carolingian times, and they refer to the darkness during the Crucifixion: “Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over the whole earth, until the ninth hour” (Matthew 27: 45). The darkness is represented here by the purple clouds. Here we also see the idea that the celestial bodies stood as witnesses for all of creation, mourning the death of its Creator. At the base of the cross is a skull, a double reference that Golgotha “means ‘The Place of the Skull’” (Mark 15:22) and that it was also believed to be above Adams’s tomb. Adam’s burial directly below the Crucifixion associates Adam, whose actions caused harm to the human race, with Christ, the new Adam (I Corinthians15), who brought eternal life. To the left stands the Virgin Mary, dressed in a white wimple and blue mantle. Her head is bowed and her hands are folded in prayer. On the right is St. John the Evangelist in a purple mantle and gold robe. Mary and John are both traditional figures at the foot of the cross.

Two donors, in small format, kneel in front of Mary and John. Théodule Michel was a citizen of Bulle, the major city of the district of Gruyère in western Switzerland. He exercised the profession of notary since 1612 and served as secretary of the bailiff tribunal (curial) of Bulle in 1641 and 1643. He also held the post of banneret in 1661. We do not know Théodule Michel’s profession but he was the father of the Georges Michel (1620–to after 1677), who was a doctor of theology and priest in Bulle from 1646 to 1677. Théodule died in Bulle on January 30, 1670. He had at least two other sons, recorded as Jaques and Pierre (information provided by Leonardo Broillet, archivist of Fribourg). The person of Jean du Villard is unverified in archival searches, although BVLENSIS clearly refers to Bulle. Pierre Walleian (Vallélian) may have been of the same family as Loys Vallélian, a painter, coming from Gruyère, most probably from the village of Pâquier. The name must have originated with an individual name Valérien of Pâquier. His descendants took the given name as a family name, which evolved from Valérien to Valérian and then Vallélian (Bourceroud, 2006), pp. 121–30).

At the sides, the donors’ patron saints watch from pedestals. On the left is St. Theodule dressed as a bishop with a blue cope and miter and a yellow chasuble. In one hand he holds a crosier, with a sudarium (veil) hanging from the top (indicating an abbot), and in the other he carries a sword with the blade resting on his shoulder. Theodule was an early bishop, whose diocese was the oldest in Switzerland; the image shows the power of his successors as secular lords as well as spiritual leaders. Theodule was particularly honored in the area in the southwestern part of Switzerland, especially the cantons of Fribourg and Valais which had remained Catholic during the Reformation. The region’s conservative position can be associated with its unusual fusion of temporal and ecclesiastic. Valais, for example was actually ruled by the prince-bishops of Sion, who traced their origins through St. Theodule. At the saint’s feet, a green demon equipped with yellow testicles struggles to carry a blue bell, referring to the legend that the bishop forced a demon to carry the papal gift of a bell across the presently-named Theodul Pass. St. Peter stands on the right, wearing a blue mantle and white robe and carrying his traditional attribute, the keys. The keys are a reference to Christ’s words to Peter, “And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:19), which Catholics saw as establishing the authority of the pope.

The status of the Canton and city of Fribourg provides the context for the message and structure of this panel. At one time under the influence of Savoy, it gained independence as a Free Imperial City in 1478. In 1481, Fribourg joined the Swiss Confederation. Its government long remained under the control of a group of patrician families, who were instrumental in encouraging adherence to the old religion during the time of the Reformation. Fribourg is on the edge of the divide between Catholic and Protestant Switzerland. During the Middle Ages, the influence of the church had been strong, with powerful abbeys founded by the Cistercians, Augustinians, and Franciscans. It became a center of Counter-Reformation activity and in 1580. Aware of the Protestant schools founded at Basel, Lausanne and Geneva, the government invited the celebrated Jesuit, Peter Canisius, to found the College of St. Michel for the education of the youth. Canisius died in Fribourg, 21 November, 1597. Thus, in 1612, we see the context for so articulate a manifestation of Catholic piety and the social and religious ties among men promoted by Jesuit education.

The artist shows a sure hand in the depiction of the many components of the scenes. The grisaille matte is applied in a painterly fashion in many areas. In the robes of the Virgin and St John, for example, over a layer of medium wash, shading washes blend with few hard edges. Trace is varied among thin and broader strokes. Removal of paint is similarly varied. In the garments of the Virgin, extremely small strokes indicate her robes’ soft contours and linear work suggests the sharper edges of her veil. John’s robe and exposed area of tunic show linear accents that suggest a surface sheen. The anatomical three-dimensionality of the devil is a testimony to the artist’s sophistication.

A comparison can be made with a panel showing the Allegory of the Conflict of the Soul commissioned by Peter Hans in 1610 (Museum für Kunst und Geschichte, Freiburg, inv. no. MAHF 2451; Bergmann, 2014, pp. 566–67, no. 87; note, the man plowing is a stopgap, FR_87). We find the same general proportion of central figural scene to architecture. The patron saints, in this case Peter and Barbara, stand on red bases against light-colored pillars similar to those in the Los Angeles panel. A wide area below is dedicated to the inscription. On the left, Peter Hans, a member of the clergy, kneels in prayer, rosary beads in his hands, and his coat of arms is shown on the right. His stance is similar to the donors adoring Christ’s redemptive act in the Crucifixion. Beyond workshop similarity, common local conventions of painting and composition link the panels. The haloes of the saints in both panels are enhanced by radial striations. The subtle use of enamel colors may be the most striking common characteristic. Combining washes and stickwork, the two artists achieve a remarkably engaging reciprocity among the figures and the landscape. Although not as complex as the clouds in the Los Angeles panel, the circular-shaped clouds at the height of the tree are an eye-catching element of the 1610 composition.

Cited in:

Garland sale, 1924, no. 331.

LACMA Quarterly, 1945, pp. 5–10.

Normile, 1946, pp. 43–44.

Hayward, 1989, p. 74.

Bergmann, 2014, pp. 111–12, fig. 78

Raguin, 2024, vol. 1, pp. 19–20, 196–99.