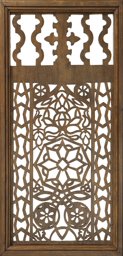

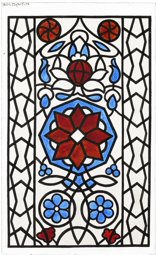

The design of this replica shows significant differences when comparison is made with Islamic stucco and glass windows. It can therefore be assumed that it was designed in Europe, by a local architect or interior designer. The most significant difference in comparison with examples from the Ottoman Empire, however, is the execution of the lattice in wood instead of stucco. A similar transfer from stucco to wood can be observed in the windows designed by the British architect William Burges (1827–1881) for the Arab Room of Cardiff Castle in Wales (IG_484–IG_487). Like these windows, the replica discussed here, as well as four similar replicas in the Wien Museum collection, was executed in a local (Austrian) workshop.

While Burges was able to draw on his first-hand knowledge of Islamic stucco and glass windows acquired during his journey to Turkey in 1856/1857, the unknown designer of the Vienna replica seems not to have not been very familiar with this type of windows or Islamic ornamentation in general, and to have opted for a very free interpretation without direct reference to Islamic prototypes.

Together with four similar replicas (IG_371–IG_374), this window was originally installed in an Arab-style interior created on behalf of the Austrian entrepreneur Anton Johann Kainz-Bindl (1879–1957). The latter travelled to the East shortly after marrying Maria Russleitner in April 1900. Together, they visited Egypt, the Near East, Turkey, and Bulgaria and acquired various art objects during their journey. To present them in a suitable setting, Kainz-Bindl had an Arab-style interior installed on the mezzanine floor of the four-storey residential and commercial building that he had erected at Währinger Gürtel 166 after plans by the Viennese architects Dehm & Olbrich. Construction work started in the spring of 1900, and the Arab Room is dated 1901 (Architektonische Rundschau, 1902, p. 71; Orosz, 2021, pp. 98, 104). With the installation of an Arab Room, Kainz-Bindl was following a trend that had become established not only in aristocratic circles, but also among the wealthy bourgeoisie, who, like the nobility, wished to present their artefacts in a specially designed Islamic-style room, thereby showcasing their cosmopolitanism (Giese, 2016; Giese, 2019).

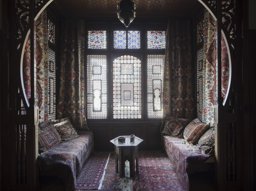

Kainz-Bindl’s Arab Room has an area of c.30m2 and is lined with wooden panelling 2.20m in height with cabinets, shelves, and cupboards for displaying Islamic objects, as well as a bay with a Secessionist entrance arch and custom-made mashrabiyyāt on three sides housing five replicas of stucco and glass windows at the top (IG_371—IG_375, see also Linked objects and images, dimensions according to Orosz, 2021, p. 104). The wooden panelling was made by Portois & Fix, a company founded in Vienna in 1881 and specializing in furniture and interior design (Orosz, 2021, p. 105). It is therefore possible that the mashrabiyyāt and the wooden lattices of the windows were produced by the same firm.

The Arab Room remained unchanged in the patron’s family for over 100 years. It was then acquired by the Wien Museum from the Viennese jewellery and enamel artist Ulrike Zehetbauer (born 1934), the wife of Kainz-Bindl’s grandson, in 2015. In 2017, it was displayed in the exhibition ‘ISLAM in Österreich – Eine Kulturgeschichte’ at Schallaburg Castle (Schollach, Austria). The bay window with its five replicas has recently been reintegrated into the permanent exhibition of the Wien Museum, which reopened in 2023 at its new location on Karlsplatz in Vienna (Orosz, 2021, pp. 98–99).