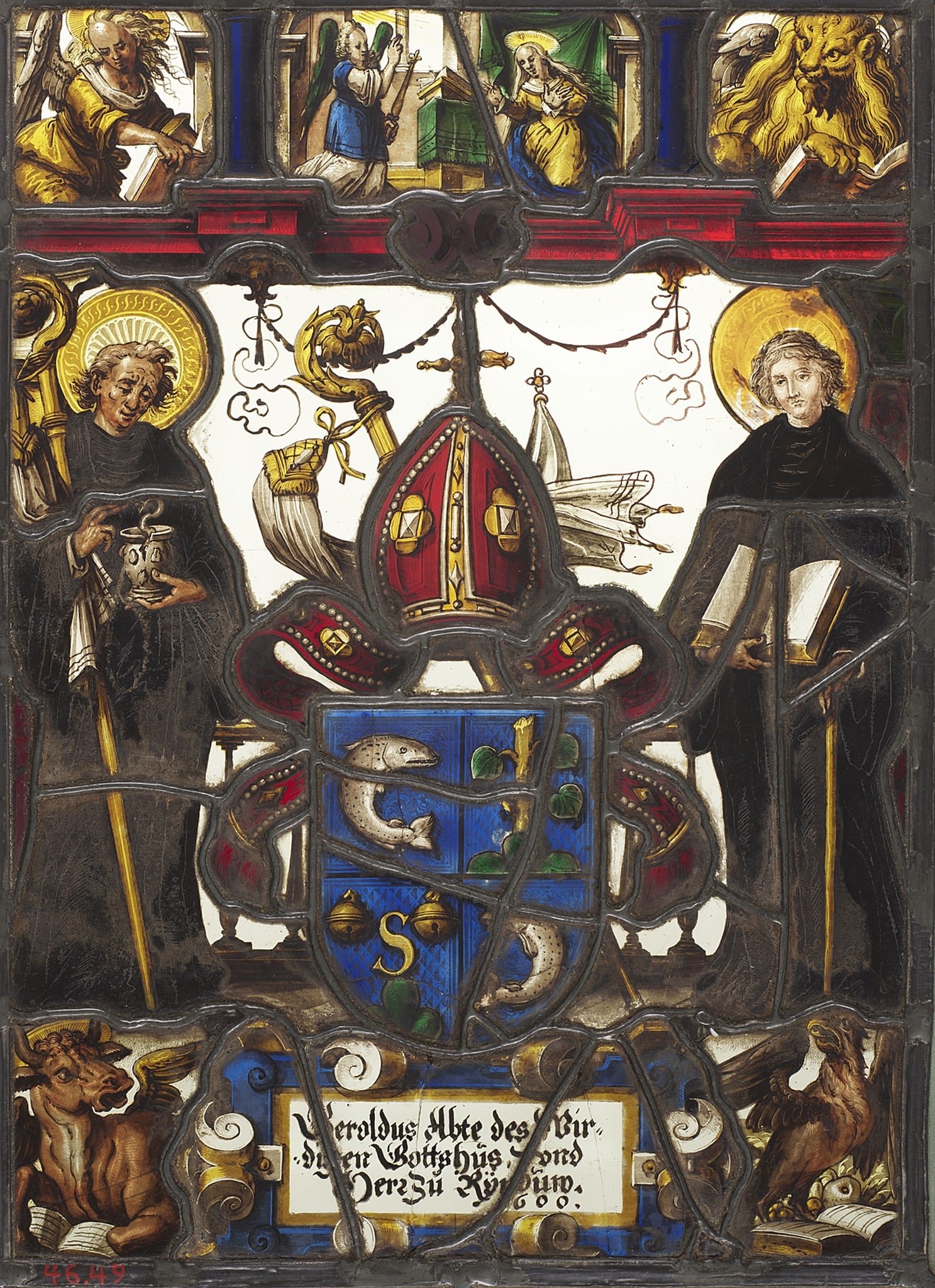

Silhouetted against a white ground, a blue coat of arms surmounted by a red miter dominates the composition. To the left and right, dressed in dark monastic robes stand saints Benedict and Fintan. Benedict, on the left, holds a cup with a serpent and a crosier; Finton holds an open book and a walking stick. A segmented red lintel is above them. Symbols of the Four Evangelists occupy the four corners, at the top reading from left to right, Matthew and Mark, and at the bottom, Luke and John. All hold books. Except for John’s eagle shown in a full rendering, the symbols are depicted by their upper torsos. In the center, above the lintel, is an image of the Annunciation showing Mary kneeling and reading a prayer book on a stand. The inscription panel below the arms is framed by three-dimensional scroll work rendered in blue and gold.

11H(FINTAN) · male saints (FINTAN)

11H(JOHN) · the apostle John the Evangelist; possible attributes: book, cauldron, chalice with snake, eagle, palm, scroll

11H(LUKE) · Luke the evangelist; possible attributes: book, (winged) ox, portrait of the Virgin, surgical instruments, painter's utensils, scroll

11H(MARK) · Mark (Marcus) the evangelist, and bishop of Alexandria; possible attributes: book, (winged) lion, pen and inkhorn, scroll

11H(MATTHEW) · the apostle and evangelist Matthew (Mattheus); possible attributes: angel, axe, book, halberd, pen and inkhorn, purse, scroll, square, sword

11I411 · the evangelists writing

46A122(ZURLAUBEN) · armorial bearing, heraldry (ZURLAUBEN)

73A522 · the Annunciation: Mary sitting

Arms of Zurlauben, Gerold I: Quarterly, 1 and 4 azure a fish argent (Rheinau), 2 pourpure on a triple mount vert a tree branch couped and leafed proper (Zurlauben), 3 pourpure on a triple mount vert an S argent between two bells or; crest: abbot's miter, crozier, and stole floating.

Geroldus abtt des wirl digen Gottshiis undl Kloster Ryhnaou 1600 (Gerold I Zurlauben, Abbot of the honorable Monastery and Cloister of Rheinau 1600)

none